Stava tailings dam failure

Stava tailings dam failure, near Trento, Italy

Figure 1: A monument built in the village of Stava, Italy

Introduction

At 12h:22':55" on 19th July 1985 the bank of the upper basin gave way and collapsed onto the lower basin, which, too, collapsed. The muddy mass composed of sand, slime and water moved downhill at a velocity approaching 90 km/h, killing people and destroying trees, buildings and everything in its path, until it reached the river Avisio. Few of those hit by this wave of destruction survived.

Along its path, the mud killed 268 people and completely destroyed 3 hotels, 53 homes, and six industrial buildings; 8 bridges were demolished and 9 buildings were seriously damaged. A thick layer of mud measuring between 20 and 40 centimetres in thickness covered an overall 435,000 square metres over 4.2 kilometres.

Approximately 180,000 cubic metres of material poured out of the dams. A further 40,000 - 50,000 cubic metres came from erosion, buildings demolished by the flow and hundreds of uprooted trees. The July 19th 1985 disaster in the Stava valley was the most tragic of its kind. With its toll of 268 lives lost and 155 million Euros in damage, it was one of the worst industrial catastrophes in the world, second in Italy only to the Vaiont tragedy.

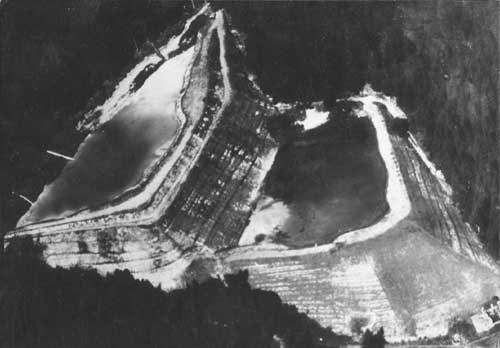

Figure 2: Aerial view of the aftermath

The Cause

Over a period lasting more than 20 years, the tailings dams underwent no serious stability checks whatsoever or any other monitoring by Public Departments obliged to supervise safety levels in order to guarantee safety to the mines and nearby communities.

In 1974, the Municipality of Tesero asked for checks to be carried out in order to assess the safety of the dam. The Mine Bureau of the Autonomous Province of Trento entrusted the licensed company (Fluormine, which belonged to the Montedison and Egam groups at that time) with the task of carrying out these checks. They were performed in 1975.

Although a number of vital checks were not made, it was established that the bank of the upper basin was "exceptional" and that its stability had been taken "to the limit". In his first report the technician carrying out the checks goes on record as saying: "it's hard to believe that they are still standing". In any case, Fluormine's response to the Mine Bureau, and the latter's response to the Municipality of Tesero was positive. This was followed by more waste being poured into the basin, marked by a lower degree of inclination.

Figure 3: Aerial view of the dams before failure

The ministerial Commission of Inquiry and the experts appointed by the Law Court of Trento ascertained that "the settlement system as a whole constituted a continuous threat looming over the valley. The system collapsed because it was designed, built and managed in such a way as not to provide the security margins that society expects of constructions liable to threaten the existence of entire communities. The upper bank was bound to collapse as a result of the slightest alteration to its precarious balance".

According to the subsequent inquiries, the collapse was caused by the chronic instability of the dams, especially in the upper one, which were below the minimum factor of safety required to avoid collapses. In particular, the causes of instability were found to be as follows:

- Deposited slimes had not settled for the following reasons:

- The marshy nature of the soil on which the dams were built, where it was impossible for the mud to settle;

- The bank of the upper basin was not built correctly, and therefore made drainage very difficult;

- The upper basin was built very close to the lower one: as the bank continued to grow, it began to spread to the unsettled slime in the lower basin;

- This made drainage more difficult and stability more precarious.

- Excessive height and inclination of the dams:

- The bank of the upper basin measured 34 metres in height;

- Inclination reached 80 per cent, in other words a 40° angle;

- The tailings dams were built on a slope whose average inclination was approximately 25 per cent;

- The decision to enlarge the bank according to the "upstream" method, which was the quickest and most inexpensive, but also the most dangerous;

- The drainage pipes were installed incorrectly (on the basin beds and through the banks).

Figure 4: Mudflow through the town

The trial

The trial ended in June 1992 when 10 people were convicted of multiple manslaughter and culpable catastrophe, in other words:

The following parties, since they were regarded liable owing to the conduct of their employees, were convicted to liquidate damages:

Figure 5: During the court trial

Besides the actions omissions considered relevant from a criminal point of view, the Stava Valley disaster was also caused by behaviour transcending the legal dimension. For instance, there were decisions by the licensed companies and public bodies entrusted with safeguarding the territory and the safety of the people which favoured economic profits instead.

Figure 6: List of the 268 people who died shown during the court trial

References

All the above text and pictures are courtesy of ‘Foundation Stava 1985’ http://www.stava1985.it

Tosatti, G. (2003). "A review of scientific contributions on the stava valley disaster (Eastern Italian Alps), 19th July 1985".